by

A. C. C. Thompson (1821-1877)

BEING A TRUE ACCOUNT OF THE VOYAGE AND

SHIPWRECK OF THE AUTHOR.

Written for The Central Georgian, in the year 1859.

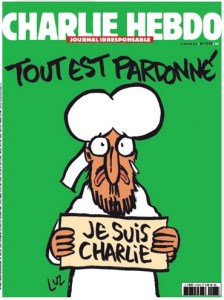

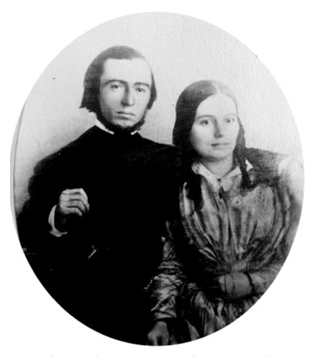

A. C. C. THOMPSON and his wife Sarah Haddaway around the time of their marriage in 1844, the year after he returned from his voyage. He would have been about 33 years old.

INTRODUCTION

“Incidents of a Whaling Voyage”, was written by my great-great-grandfather, Dr A. C. C. Thompson, in a series of articles for a Georgia periodical in 1859, sixteen years after his return to America. It came to me in the form of a pamphlet published with a Forward by his grandson James Wooten McClendon Jr in the mid-20th century, exact date unknown. His forward will serve to introduce the author.

In creating a digital file of my great great grandfather’s story, I have refrained from exercising an editorial hand, with the following exceptions:

• Where he has spelled the same word differently in different places, I have settled on one spelling with a preference for current practice.

• Frequently the names of geographic locations have changed over the intervening 180 years, and in those cases I have substituted the modern name or spelling.

• For the sake of clarity I have added or subtracted a word here and there.

• I will confess to having eliminated a lot of commas and semicolons where they seemed unnecessary. I know I have done the same with my own writings; I think we were trained to sprinkle them everywhere, y’know, back in the day.

• I assume that all the poetry is his; whether composed during the voyage or later I do not know.

Having said all that, this narrative remains a remarkable document of this young man’s wanderlust. Once he set foot on the whaling ship Cadmus and watched the coast of Massachusetts disappear over the horizon, this new medical school graduate, not yet 20 years old, stepped into an entirely different world than the one he grew up in, for the life of a common sailor on a 19th century whaling ship was no picnic.

One hundred forty years later I myself, with likewise very sketchy credentials as a seaman but apparently a genetically-inherited wanderlust, sailed into the very same harbor of Pape’ete, Tahiti….for that story see my post “The South Pacific”.

Dr A. C. C. Thompson is the character in my family history that I am most invested in exploring and documenting. Another writer — Gary D. Crawford — laid the groundwork for my interest in a series of articles for the Tidewater Times of Chesapeake Bay 2016-2019, one of which, “Global Links”, he was kind enough to allow me to reprint here on my blog before he passed away in 2020.

I hope in the future to flesh out the history that Mr Crawford sketched out, explore and maybe answer some of the perplexing questions he posed to me back in 2019, and address the role that slaveowners played in the midlands between North and South at a time that slavery was perhaps the number one topic of national debate and about to plunge the country into a bloody civil war; and for me personally, the question of how we, the descendants of slaveholders could, should, would or might look back on all this….and move ahead.

Joseph McClendon Stevenson, Astoria, Oregon, July 2025

FORWARD

Dr. A. C. C. Thompson, my maternal grandfather, was born in Talbot County on the Eastern shore of Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. He was the only child of Dr. Absalom Thompson, a prominent physician, who had a large colonial residence on a large tract of land, known as Webbley, or Mary’s Delight, fronting on the bay. There, Dr. Thompson established and operated a hospital, the only institution of that nature in that vicinity. The building is still there and well-preserved with some minor alterations and additions. A history and description of it is published in the March, 1954 edition of the Maryland Historical Magazine. The Bay front of the building is pictured on the front cover.

Grandfather Thompson was born October 12, 1821. He was named Absalom Christopher Columbus Americus Vespucius Thompson. According to family tradition, his father wanted him named for himself and the discoverer of America; and, since at that time, there was a dispute as to which was the real discoverer, he named him for both. Later, the son dropped “Americus Vespucius” from his name.

He was graduated in medicine from a Baltimore college. Shortly thereafter he was sent to Massachusetts on a business mission. After its accomplishment, and at the urge of an innate wanderlust, he apprenticed himself to a whaling schooner for a three year’s voyage to the Pacific. Being under 21 years of age, he registered under the assumed name of “Charles Rochester from Easton, age 22, height 5’ 3¾“, light complexion, sandy hair.”

Dr. Thompson was in the Marquesas Islands when the French took possession in May, 1842 (See Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. 14, page 939, 14th edition, 1920). He spent nearly three months in Tahiti, whence he sailed on an English boat bound for Chili or Peru. This must have been about September or October, 1842. According to a statement by my mother, he travelled overland across Brazil to some port on the Atlantic or Caribbean, whence he returned by ship to Maryland, arriving after his father’s death. He claimed his father’s bequests and engaged for a while in a mercantile adventure, which was not very successful, in Wilmington, Delaware. On May 3, 1844, he married Sarah Ann Haddaway, a descendant of two prominent families of Maryland, the Webbs and the Haddaways.

Three girls and a boy were born to them. The oldest, my mother, was born April 1, 1845, in Wilmington, Delaware, as were the two other girls. The son, George Calvert, was born April 23, 1853, after the family moved to Burke County, Georgia. He was ordained by Bishop Pierce, as was his father, as a minister of the Methodist Church, South.

Dr. A. C. C. Thompson served as a surgeon throughout the Civil War in the Third Georgia Regiment. He preferred teaching to practicing medicine, however, and established a number of schools in various parts of Georgia. Among them, one at West Point where my mother was one of the teachers and married my father who was mayor of the town. The school was later transferred to the public school system of West Point. (See West Point in the Chattahouchie, 1920, pages 88-89.)

James W. McClendon

Incidents of a Whaling Voyage

On a clear and cold morning — November 11th, 1841 — the good ship Cadmus weighed anchor and departed from the harbor of Fairhaven, with a free quarter breeze and a flowing sheet, on a whaling voyage to the Pacific.

There is generally a peculiar feeling of mingled anxiety and expectation which impresses those about to start on a long journey; but on leaving our native land to be absent for years, and probably never again to return, there is an indescribable gloom which comes over the soul and burdens the heart with sadness.

As we moved gracefully down the Bay, the houses and spires in the towns of New Bedford and Fairhaven gradually faded in the distance, and in a few hours we were upon the bosom of the Atlantic, leaving the shores of Massachusetts as a faint blue outline on the western horizon.

I bade my native land farewell

And turned on other thoughts to dwell;

But oft’ there would a vision come,

On memory’s view of happy home.

My happy home! when shall I see

The sacred place so dear to me?

Thy imagery shall ne’er depart,

From the fair tablet of my heart.

The first regular business after clearing the Bay and dismissing the pilot, was to choose watches; and as this may not be understood by many of my readers, I beg leave to explain.

The business on board of a ship is conducted with the strictest discipline. The crew is divided into two sections or watches called the starboard and larboard watches. The terms starboard and larboard mean the right and left side of the ship, and as the starboard side of the quarterdeck is appropriated to the commander, the watch which is under his immediate command, or under his chief officer, is called the starboard watch, and that which is under the control of the second officer or mate is called the larboard watch.

Our crew consisted of 38 men all told including the Captain, 4 Mates, 4 Boat Steerers or Harpooners, Carpenter, Cooper, Steward, Cabin-boy, Cook, and 24 men before the mast, i. e., the common sailors, among whom was your humble narrator. According to custom, the men were mustered aft, and the first and second mates selected alternately until the crew were divided into watches as before mentioned, after which the Captain lectured the crew briefly upon the importance of strict discipline. The starboard watch was then called on duty and the larboard watch retired below, some of them to take their first rocking slumber upon the briny ocean.

To give some idea of the strict regularity that is observed in all the business and evolutions of a well regulated ship, I will now state the duties of the watches and the general character of the nautical government. In designating time on ship board, instead of mentioning the hours of the day, we designate them by watches and bells according to the following regulation:

The sea-day of 24 hours is divided into 4 regular watches of 4 hours each, and 3 short watches of two hours each called the dog watches. The time in these watches is divided into bells; that is, there is one tap given to the watch bell for every half hour during the watch, so that 8 bells make a complete watch and 4 bells make a dog watch. Therefore when 8 bells strike, one watch goes off and another watch comes on duty. If a sailor wishes to tell that anything occurred on Thursday at 10 o’clock, a. m. he says “on Thursday at 4 bells in the forenoon watch”. Only one officer exercises command during a watch; for instance the first mate commands the larboard watch and when he is on duty he is said to be the officer of the deck. The same is said of the second mate when he is on duty with the starboard watch. When the officer of the deck gives a command, it is given in a very positive manner, and the sailor must always answer “Aye, aye Sir,” and obey the order immediately, without asking why or questioning its propriety. I will now mention some rules of etiquette on board of a whale ship, which are as rigidly observed as the rules of a monarch’s court.

All that part of a ship’s deck abaft the mainmast is called the quarter-deck. The officers generally occupy this part of the ship, and the sailors never come upon the quarter-deck, unless to perform some duty. When a ship is at moorings or running before the wind, the starboard side of the quarter-deck is reserved for the captain or for the officer in command, and the other officers confine themselves to the larboard side. When the ship is sailing upon the wind, then the Captain or officer in command occupies the weather or windward side and the other officers the lee side. When a sailor goes aft on duty, he must never walk upon the quarter-deck which is appropriated to the commander unless his duty compels him to go upon that side.

When breakfast, dinner, or supper is ready, the Steward always makes the announcement first to the Captain, and then to each officer in regular succession according to rank, allowing nearly a minute to intervene between each announcement.

Spitting upon the deck is strictly forbidden, and when an officer or seaman wishes to spit he must always go to the lee side.

DAWN AND SUNRISE.

Nothing can exceed the beauty of day-dawn and sun-rise at sea when the weather is clear and moderate. On the morning of our second day at sea the sky was cloudless, with a very light breeze from the westward; the ship alternately rose and descended with a slow, graceful motion upon the long rolling waves, which were scarcely ruffled by the gentle breeze. A profound silence brooded o’er the ocean, and the sweet stillness was only broken by the flapping of the sails against the spars, the creaking of the rudder and the measured tread of the watch as they paced upon the deck. A faint grayish streak was seen on the eastern horizon, gradually brightening into a mild silvery light which kissed the tops of the slow rolling waves. The dawn rose higher, spread wider, and grew brighter, until a soft holy light was spread over the visible surface of the ocean. Next a roseate blush was diffused over the eastern horizon, and soon the glorious sun rose majestically from his liquid bed, pouring a flood of sparkling light upon the surface of the ocean, without a single object except the ship to intercept his beams. I have witnessed many lovely dawns and sun-risings at sea, but the first made an indelible impression upon my mind and feelings, and was sufficient to compensate for many unavoidable privations.

The silvery beams of morning light

Come, gently stealing on my sight;

Then, orient blushes light the sky,

With loveliest hints of roseate dye.

Now rising from his watery bed,

The glorious sun his radiance shed;

And with a flood of light he laves,

The ambient sky and rolling waves.

THE FIRST STORM.

As we approached the Gulf-stream on the evening of the second day, the heavens gradually assumed a foreboding aspect. The sun went down behind heavy banks of leaden clouds whilst a thick vapory curtain hung around the eastern horizon. That night during the latter part of the evening watch, the alarm bell rung, and all hands were called in great haste to take in sail. As soon as we waked we heard the roar of the tempest, the loud commands of the officers, and the tumultuous trampling of the watch upon deck; whilst the ship was pitching and plunging as if she were trying to jump from under us. We rushed upon deck and found everything in confusion. A violent gale was blowing from out of the East, the rain descended in liquid sheets, and the mountain waves were rushing and foaming, as if the ocean was angry at being thus disturbed in the solemn hours of the night.

Our noble ship was careering gallantly over the waves with the white sails fluttering in the gale; the yards had been hastily lowered upon the caps, and the sails clewed up, which caused them to flow loosely and soon, the sailors were in the rigging and upon the yards, pulling and hauling; which, with the stern commands of the officers, and loud responses of the seamen heard above the roaring of the tempest, and all mingled with utter darkness, presented a scene of confusion and consternation, unequaled to those who had never witnessed it before. During this confusion a huge foaming wave broke over the larboard quarter, submerging the deck and sweeping off one of our boats from the cranes.

However, the ship was soon put in proper trim; the spanker was closely brailed, the top gallant sails, staysails and jibs were furled, and the ship laid to under double-reefed main and fore topsails.

Our gallant ship bent to the blast,

And felt the shock through hull and mast;

She leaped and plunged like some huge beast,

That struggles hard to be released.

The howling tempest and the rain,

Rushed madly o’er the watery main;

Whilst night’s dark curtains circling ’round,

Rendered the horror more profound.

The storm began to abate during the morning watch, and soon after day we made all sail and steered South East, intending to touch at the Cape Verde Islands.

Perhaps it will be proper to give some description of our officers and crew, inasmuch as I shall have frequent occasion to introduce them during the voyage. Our commander Captain Mayhew was a man of some piety, and a member of the Baptist church. He was a strict disciplinarian, but very mild in his administration; and not only forbade all profane language among the officers and crew but discountenanced all filthy and vulgar practices. As an example of his manner of reproving the officers or sailors for swearing, I will relate the following incident: On one occasion, the third Mate commenced swearing vehemently at some of the sailors, and Captain called the Steward, and handing him a cup of water and a piece of soap bade him take it to Mr. Crowell, with the request that he would wash his mouth. The third Mate felt the reproof, very sensibly, and was careful that the Captain should not hear him swear again.

Our Mate — Mr. Norton — was an excellent seaman, a good scholar, and a gentleman of considerable refinement. He was a better navigator than the Captain. Our second Mate,—Mr. Fish — was a noble-hearted sailor, and a good officer, but his education and accomplishments were very limited.

The third Mate — Mr. Crowell — was profane and vulgar, and possessed very few good qualities to recommend him. The fourth Mate — Mr. Chase — was an illiterate man, but he possessed good principles and was an enterprising officer. We had 4 Boat-Steerers, or harpooners — a kind of second class officers whose duties were to steer the whale boat, harpoon the whale, and take part in the general exercises of working the ship. Among these we had one low dissipated fellow — a Portuguese — but the other three were clever active young men, who generally conducted themselves very well. Our Cooper was a stern old seaman, possessing great physical powers and ever ready to brave any danger, as will appear in some of my subsequent narratives. The Carpenter of our ship was a tolerably smart man, who had seen much of the world. He would sometimes remark, “Well boys, I served two years on board of a privateer, was taken prisoner and stowed away in a prison ship in England; I served in the Florida war, I have had several narrow chances of being sent to the penitentiary, and now I am on a whaling voyage; what will come next, the Lord only knows.” Among our crew we had only three men who loved rum excessively; the others were temperate or moderately so, and were all active and obedient except one Portuguese, who was passionate and stubborn, and a young man from New York, who was so lazy and entirely worthless, that he was rejected and sent home. Among the common sailors was a very pious young man of the Methodist persuasion — James Hutchens of Fairhaven, Mass. There were ten experienced seamen before the mast and fourteen green hands who had all the nautical operations and whaling business to learn. Besides the regulars, we had on board Dr. Wells, passenger to Tahiti.

Our ship was strong and well equipped, and with such a crew as I have briefly described, we started for the Pacific on a three years whaling cruise. Our chief occupation during the early part of the voyage, was to work the ship, keep the rigging and sails in good order, look out for whales, and occasionally, when the weather was moderate, the boats were lowered, and the men drilled in rowing and the usual whaling tactics. Dr. Wells and six or eight of our green hands suffered considerably for several days from seasickness, but in the course of 10 or 12 days they had all recovered from their sickness, and were able to partake of the rough sea diet and perform their regular duties with alacrity.

After the storm which I have already described, nothing very interesting occurred, until we arrived at the Island of St. Nicholas, one of the Cape Verde group near the coast of Africa. In the afternoon of Dec. 7th, the joyful cry of “Land ho!” sounded from the main lookout. “Where away?” cried the officer of the deck. “Three points off the lee bow!” responded the lookout. The Mate then went aloft with spy glass, and in a short time made it out to be the Isle of St. Nicholas, distant about 35 or 40 miles. We were running down the trade winds on the larboard tack, with a stiff quarter breeze and making about eight knots per hour. Most of the officers and sailors ascended the rigging to get a sight of the desired object, which was seen like a blue cloud upon the southern horizon. Gradually it became more distinct, until the separate peaks of the mountains, and the deep gorges and valleys began to appear, and the blue hazy tint by degrees assumed first a pale and then a deep brown color.

We had been 27 days at sea and had seen no land since we left the shores of Massachusetts; consequently many of us were much rejoiced by the sight of terra firma. When we had approached within three or four miles of the Island, we ran down the eastern side to enter the Port.

This Island presented a novel feature to those of us who had never seen mountainous land. The whole Island appeared to be a mass of mountains presenting in the interior four or five prominent peaks about 6000 feet high, which gradually sloped to the ocean, with many gradations of hills and valleys, to break the regularity of the slope. There are eleven islands belonging to this group extending from 14½ to 17% degrees North Latitude, and situated about 400 miles from the West coast of Africa. They belong to Portugal, are inhabited by a mixed race of Portuguese and Mulattoes, and are of very little commercial importance; being so sterile as barely to yield a scanty subsistence for the inhabitants. Some of these islands carry on a very limited trade in salt, which they procure by evaporating sea water. Our object for stopping at St. Nicholas was to procure a supply of pigs, poultry and vegetables, which we purchased at reasonable prices in exchange for sea bread, soap, calico, etc. Finding that we could not enter before dark, we “lay off and on” during the night and early in the morning stood in for the Port. As we neared the land, we beheld the surf beating violently against the rocky shore; and finding the Port very narrow and incommodious, we did not enter, but sent two boats ashore, whilst the ship laid to in the offing. On landing, we found the beach crowded with a promiscuous throng of men, women and children, most of whom were poorly clad, and appeared to have been but scantily fed. Many of them had come from the interior, bringing with them various articles of produce, which they were anxious to sell to our Steward. There was a small collection of houses; some of them built of rock, and some of sun dried brick, having roofs thatched with plantain leaves. As there was nothing about the Port to interest us, we made up a party of nine to visit the town of St. Nicholas situated seven miles in the interior. Our party consisted of the Captain, second Mate, one Boat- steerer, Carpenter and five sailors; the third Mate and three sailors being left to take care of the boats, whilst the Steward made the purchases. I was placed with those who were to watch the boats, but I succeeded in hiring one of the sailors to remain in my stead, and I obtained permission to accompany the party to the town.

VISIT TO THE TOWN OF ST. NICHOLAS.

By taking a foot path over the mountains, the distance from the Port to the town of St. Nicholas was only four and a half miles; whilst it was seven miles by the road. We determined to take the route over the mountains, that we might enjoy the scenery and therefore hired a Portuguese lad for a guide. For nearly a mile the ascent was gradual, not rising more than 800 feet above the level of the sea. This portion of the Island might properly be called table land; or rather, several belts of table land, with a red silicious soil, considerably intermixed with gravel. We passed a few rude cottages upon this table land surrounded by small barren fields or patches, which were walled in white stone for there is scarcely any wood upon the Island. We saw numerous flocks of goats, and occasionally a few diminutive donkeys, feeding upon the scanty herbage, but there were very few indications of intelligence or industry. It appeared that their agricultural enterprise never exceeded a patch of corn and yams, and occasionally a little sugar cane.

After leaving the table land, our guide led the way over steep and rugged hills; and as several of our party wore sailor’s light pumps, or slippers our feet began to feel the effects of the rough gravel. Nevertheless, we wended our toilsome way up and down the precipitous hills; occasionally crossing small green valleys, where the orange and banana trees afforded us refreshing shade, but very little fruit. It is only in those little valleys where the soil is fertile, springs afford the means of irrigating, that anything of much consequence can be produced for the sustenance of the inhabitants; and the valleys bear such a small proportion to that which is barren, that probably not more than one twentieth part of the whole Island is susceptible to cultivation.

After nearly two hours toiling and occasionally resting we reached the highest part of the mountain over which our path led; probably about 5000 feet above the ocean; but there were several peaks from 800 to 1200 feet higher than the part over which we passed.

From this elevation we had a magnificent view of the ocean. We swept the horizon with a scope of 70 or 80 miles towards the East and South East, and through several deep gorges we had a view of the ocean on the Western side of the Island. As there was scarcely wind sufficient to ruffle the surface of the ocean, it appeared like a vast expanse of liquid glass, the nearer parts rising and falling with slow glossy undulations, whilst the more remote faded into a misty blue until it appeared to mingle with the sky. The ocean, under all circumstances, possesses a sublimity on account of its vast extent, its profound depth and its ceaseless motion, but its sublimity is greatly increased when, from a great elevation we survey at a glance about 4000 square miles of its surface, and then consider that as vast as may appear the area of our vision, it comprises scarcely a unit of that interminable waste of waters. The houses in the Port which we had left about two hours previous, now appeared as mere dots upon the sea-shore; and our ship in the offing appeared like a diminutive toy boat.

I had never before ascended a mountain, and indeed there was such a wild grandeur in that mountain scenery, that notwithstanding the sterility of the Island, I formed an attachment for it which did not altogether depart, even when I had visited more interesting places.

After we had rested a few moments and enjoyed the fine prospect around, above and beneath us, we commenced our descent on the other side of the mountain, passing over hills and valleys as we had done in our ascent, but we found the valleys more fertile than those on the side next the ocean. Unfortunately, our guide could speak only a few words of English, and none of our party understood the Portuguese language; consequently, we could gain no information from him respecting the Island.

After pursuing our winding path over hills and valleys; sometimes fording little mountain rills, and sometimes passing along steep ledges where the precipitous chasms below us were several hundred feet deep; we at length came to the inner brow of the mountain ridge, and our guide pointed out the town about five or six hundred feet below us in a pleasant valley. As we were anxious to terminate our fatiguing journey and, get some refreshments; we hurried on, and in a short time entered the town of St. Nicholas. It is a small town extending irregularly about half a mile along the valley, and presenting few appearances of comfort or delight. The houses are small and roughly built of stone or sun-dried brick, with small windows generally about one and a half by two feet, and presenting many appearances that indicated the slothful and filthy habits of the occupants. There were not more than six or seven dwellings and a small Catholic Church that looked even tolerably respectable. The situation of the town is very pleasant, serene, well shaded with orange, lime and banana trees; but unfortunately the inhabitants are deficient in the three great elements of improvement: intelligence, enterprise and capital. Three of our party called on the Commandant of the island, a meagerly consequential little man, who appeared to feel the full responsibility and dignity of his office. He treated us to excellent fruit and sweet wine, and made many inquiries about such simple things as we supposed every man of ordinary intelligence ought to know. Nevertheless, notwithstanding his limited means and apparent ignorance, he was as much elated with official honors, as if he had been a genuine Braganza.

A few hours sufficed for us to see all that was interesting in the town of St. Nicholas; and feeling too much fatigued to retrace our steps over the mountains, we hired some donkeys and drivers to return by the road. Donkeys and mules are the only beasts of burden used in these Islands; the roads through the mountains being so rough and precipitous that no other animals used for traveling can pass upon them. The donkeys upon which we rode were not more than one third as large as an ordinary mule; and they were so gentle that they were ridden without bridles, and directed by words and blows on the neck and head with a small paddle. We were unable to talk to the donkeys and manage them like the natives; some of our party therefore proposed that each of us procure a head of cabbage or bundle of hay and hold it before his beast on the end of a pole, presuming that the animal would follow it. As this suggestion appeared more amusing than practicable, we did not put it into execution but trusted to our drivers, who by frequent blows and much hallooing got us down to the Port in a little more than two hours. The valleys along the road were more fertile than those we crossed in our path over the mountains. Besides the usual tropical fruits we saw considerable coffee, and some luxuriant crops of corn and beans, and a very large variety of squashes. We saw on the roadside a large wooden cross, erected over a pile of stones, and on inquiring of one of our drivers who could speak some English; we learned that it was the grave of a man who had been robbed and murdered at that place. I afterwards discovered that it was a common practice among Spaniards and Portuguese in Catholic countries, to erect crosses over the graves of murdered persons.

When we returned to the Port, we found that our Steward had obtained a good supply of pigs and poultry; and having no other business to delay us, we immediately embarked and reached our ship before sunset, hoisted the boats, set all sail, and bore away for the coast of Brazil.

Once more we bid the land adieu,

And spread our canvas to the breeze;

With buoyant hopes our course pursue,

To capture whales in Southern Seas.

Our gallant ship with full spread sails,

Before the gentle trade wind moves;

But higher waves and fresher gales,

Are what a noble sailor loves.

We left the Island of St. Nicholas on the evening of Dec. 8th; and running almost directly before the trade winds we crossed “the line” Dec. 17th. As some of my readers may not understand what is meant by “the line,” I will explain that it is a term used by sailors to designate the Equator, which to every intelligent reader is known to be the imaginary line or circle with which geographers divide the Earth into Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Many years ago it was a very general practice among seamen, to play amusing tricks upon greenhorns, by making them believe that Neptune always came on board and shaved those who had never crossed the line; consequently, when a ship approached the Equator, a sailor was generally disguised to represent Neptune, and the affrighted green ones had their faces smeared with slush-grease and scraped with a piece of hoop iron. However this practice has entirely ceased, and is almost regarded as a nautical legend.

We had now entered the Southern Hemisphere; many of the Northern constellations had disappeared, and new ones had arisen above the Southern horizon. In a few days we approached the Tropic of Capricorn and had the sun directly over our heads at noon, and very soon he declined to the North and cast the shadows to the South. I can scarcely realize the fact that whilst I had midsummer under the blazing sun of the Tropics, my friends in the United States had midwinter.

How wondrous are thy works, O God Most High,

Who ruleth all things in the earth and sky:

The summer’s scorching sun, and winter’s cold:

And all the beauties which Thy works unfold.

On land or sea, on mountain or in vale,

In the soft zephyr, or the rushing gale;

We see Thy power and wisdom everywhere,

And all things show Thy providential care.

After leaving St. Nicholas, a constant watch was kept at the three mast heads for whales. We saw none of the right kind until we came to the mouth of the Rio de la Plata. We frequently saw the spouts of whales, and sometimes passed very near them; but they were either the fin-back or hump-back varieties, which were not the kind generally taken by whale ships.

The two varieties of whales that are taken by whale ships are the sperm and right whale. Sometimes the hump-back whale is taken in bays and sounds on the West coast of South America by whaling crews who go out from their fisheries on shore. The sperm whale is most valuable on account of the spermaceti, and the superior quality of the oil; and ships that go in pursuit of the sperm whale do not pursue the right whale and vice versa, because they are found in different latitude; the sperm whale being found from the Equator to 35 degrees North and South; whilst the right whale is generally found in parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, ranging from 30 to 60 degrees North and South latitude. The different varieties of whales are recognized by their manner of spouting, and the shape of their backs and heads, when seen on the surface of the ocean. The sperm whale makes a low, bushy spout about five feet high, and projecting considerably forward; whilst the right whale throws a forked perpendicular spout to the height of ten or twelve feet. Whales do not spout pure water as some persons suppose, but what is termed their spout is nothing more than their breath surcharged with watery vapor as we sometimes see from the nostrils of the animals on a frosty morning, and it can be seen under favorable circumstances nearly three miles.

THE FIRST CAPTURE.

Before relating my first adventure with the spouting sea monster, I will briefly describe some parts of a whale ship’s equipment so as to render the adventure more intelligible.

The small boat which is lowered from the ship to pursue and attack the whale is about 24 feet long and five feet wide in the middle, built very light and sharp at both ends. The boat is propelled by five oars and steered by a long oar projecting from the stern, by which she can be turned round very quickly. A little abaft the middle of the boat is placed a tub containing about 150 or 200 fathoms of rope about as thick as a man’s thumb, called the tow-line, which is attached to the harpoon. When the harpoon is darted into a whale, the frightened animal plunges into the depth of the ocean with frightful rapidity, taking out the towline so rapidly, that it is necessary to keep it wet to prevent ignition as it passes through the chocks. Besides the harpoons, which are used to fasten on to the whale, long lances are carried in the boats to kill the annual after he has become worn down by his running and fright, and the boat is pulled up to him. It is the business of the harpooner, who always pulls the forward oar, to dart the harpoon into the whale, and the officer who commands the boat has the honor of killing him with the lance.

On a certain day, when we were nearly in the latitude of the Rio de la Plata, soon after dinner the repeated cry of “There she blows!” resounded from the mizzen look-out and was soon repeated from the main and foremast. “Where away?” hallooed the officer of the deck. “Off the lee beam,” responded the look-out. The ship was running close hauled upon the starboard tack, with a strong topgallant breeze and consequently making pretty rapid headway. The fore topsail was thrown aback so as to stop the headway of the ship, whilst several of the officers went aloft to reconnoiter. They soon decided that it was a school of sperm whales, and the Captain gave the long-desired command, “Prepare for action and lower away the boats.”

A thrill of joy ran through each heart,

From man to man the orders fly;

Each noble sailor acts his part,

As heroes fight to win or die.

Fearless they launched into the deep,

Regardless of the ocean’s rave;

With measured strokes their long oars sweep,

As swift they skim the foaming wave.

In less than three minutes after the order was given, the four boats were manned and darting over the water at a rapid rate in the direction of the whales. Each boat singled out a whale, and gave chase; but as they were running tolerably fast to windward, we could scarcely keep up with them; and in passing near the bows of the ship they became frightened, and increased their speed. After pursuing them for nearly half an hour, we were about giving up the chase, when the Mate espied a whale to the leeward, who had loitered behind the school and appeared not to be frightened. The Mate bore down upon him and in a few moments we saw his harpooner stand up to strike. Presently, we saw him dart two harpoons in quick succession, and the huge animal threw his flecks high into the air, and darted off with lightning speed. After making a short sounding he came to the surface and started to windward, carrying the boat at the rate of fifteen or twenty miles per hour. He did not run more than about four miles, before he became wearied and slacked his pace; and we saw the boat haul up to kill him. In a short time the Mate made signal for help, and each boat pressed vigorously for the scene of action; but the second Mate’s boat, to which I belonged, being the nearest when the signal was made, we arrived first. We found that the Mate had got both lances into the whale and lost them on account of the roughness of the sea; the second Mate therefore laid our boat alongside the monster who was blowing and bellowing at a terrible rate. The officer plunged his lance deep into his vitals, and he soon spouted blood which was a sure indication he was mortally wounded, he then roared terribly, and commenced running around in a large circle, plunging and lashing the sea with his huge fins and tail until the whole circle was covered with bloody foam. This is called the death flurry; and the boats always move off at that crisis so as to be free from danger. After performing those terrible death antics for a few moments, the whale turned upon his back and giving a few frightful groans or roars, he yielded up his mighty ghost. He proved to be a good sized whale, large enough to make sixty-three barrels of oil.

There are few persons, except those who have been engaged in the whaling business, that have any definite ideas of size, appearance and characteristics of these enormous animals; hence I shall endeavor to give a correct description of the sperm and right whale, the two varieties most commonly captured by whale ships.

The full grown sperm whale varies from 60 to 80 feet in length, and from 25 to 40 feet in girth, around the thickest part of the body. In shape it is well proportioned, being much rounder than fishes that are usually found in bays and rivers and having a long slender tail, with flukes from twelve to fifteen feet wide, situated horizontally, or parallel with the surface of the water. I will here remark that all the cetaceous mammals, such as the whale, grampus, black-fish and porpoise, come to the surface to breathe, and have their flukes similarly situated, that is horizontal or flat upon the surface of the water, which is different from all other fishes. The sperm whale has a large, square head, with a comparatively small under jaw. It has teeth only in the under jaw, which are about as thick as a large man’s arm, projecting about four or six inches above the jaw, and being from eight to ten inches long when extracted. I do not recollect the number of teeth in a whale’s jaw, but they appear to be sufficient to masticate a man, or even a small boat in a very short time. The right whale has no teeth, but from the upper jaw is suspended long strips of black bone like feathers on the side of a quill, which is the article commonly known as whalebone. In fact this is not bone, but a substance more analogous to horn; the real bone in the bodies of whales being white like other bone.

The oil is obtained from the blubber, which is a thick adipose tissue, situated between the skin and the muscular fibre, or red flesh, and enveloping the whole body. The blubber on an ordinary whale is about eight inches thick, and of a large whale from fourteen to sixteen inches thick. The blubber stripped from a large sperm whale is sufficient to load ten or twelve four horse wagons and will make eighty or ninety barrels of oil, while twenty to twenty-five barrels of oil and spermaceti is obtained from the head in a fluid state, making one hundred or one hundred and ten barrels of oil from one whale. Sperm whales are sometimes captured that make one hundred and fifty barrels of oil, and right whales sometimes produce two hundred barrels. There is no spermaceti found in the right whale, and hence their oil is not so valuable as the sperm whale.

After the whale was killed, the next business was to get it alongside the ship. For this purpose three boats were hitched on to it by fastening several tow-lines to the flukes, and we soon reached the ship with our first prize, though we were nearly two miles distant when the whale was killed. The whale was secured to the ship by strong hawsers and the business of cutting in or stripping off the blubber was conducted in the following manner. A powerful tackle was suspended from the mainmast, and to the end of this tackle was a very large hook called the blubber hook. One of the seamen went down upon the whale and inserted the hook into the blubber near where the head and body meet, and whilst two men stood over the side of the ship with cutting spades to cut the blubber in strips, the other seamen by the combined power of the windlass and tackle, stripped the blubber from the body. The head was severed from the body, and being too large to hoist on board it was opened alongside, and the fluid oil and spermaceti dipped out. The under jaw was then taken off and hoisted on board for the purpose of extracting the teeth, after which all the carcass was cast off, to be devoured by sharks and sea fowl. The whole process of cutting in did not occupy much more than two hours. When the head is not too large it is always best to hoist it upon the ship’s deck, so that the oil may be dipped out without spilling it into the sea; but when a whale will make even forty- five or fifty barrels of oil the head is generally too heavy to be hoisted on board. I presume that the head of a hundred barrel whale would weigh about three or four tons, or at least as much as eight or ten hogsheads of sugar.

When a dead whale is alongside the ship many sharks and sea birds are attracted to the spot, and when pieces of blubber fall off into the sea they are quickly seized by the sharks and birds. I have known whales to be captured more than five hundred miles from any land, when there was scarcely a single bird to be seen; but in less than an hour after we commenced cutting in the whale, there were probably several hundred birds around the ship, such as the petrel, shearwater, cape-pigeon, man-of-war hawk and albatross which is the largest and most beautiful of all sea birds. The albatross has a body about the size of a swan but its wings are much longer. One was taken on board our ship that measured eleven feet, from the extremities of its wings when expanded. These birds can be caught, when round the ship, by fastening a piece of blubber to a large hook, and allowing it to drift off from the ship; the albatross swallows it voraciously and is then pulled in, and it requires considerable force to manage one of these powerful birds.

The next operation to be described, is the process of trying out the oil. For this business, a large brick furnace called the triworks is built upon the main deck, containing two large caldrons, each containing about one hundred and twenty gallons. The blubber is minced, or finely sliced and thrown into these caldrons where the oil is boiled out; and when the operation commences, it does not cease by night or by day, until all the blubber that may be on board is boiled, and the oil stowed away in casks.

About seventy barrels of oil can thus be rendered in twenty-four hours. Every man belonging to a whale ship has a share of the oil, and hence each individual feels an interest in the success of the voyage. The Captain generally receives the fifteenth part; the four mates the twenty-fifth, thirtieth, thirty-fifth and fortieth according to rank; the harpooners the sixtieth, an able seaman about the eightieth, and a green hand the one hundred and fiftieth. If a sperm whale ship has a successful voyage, she generally returns with a cargo of three or four thousand barrels of oil, which is worth from $100,000 to $140,000. Of a cargo of $100,000 the Captain would receive $6,666, an able seaman $1,250 and a green hand $666, which would be the fruits of three years labor.

We took no more whales in the Atlantic, but whilst running down the coast of Buenos Aires we met a Nantucket ship that had captured two which she was then trying out. When whale ships meet, a part of the officers and crew generally pass visits which is called gamming. If the ships are sailing in the same direction, they will sometimes gam a whole day or even longer.

During the month of February, which is the last summer month in the Southern hemisphere, we arrived off Cape Horn, the most Southern promontory of South America. There we had stormy weather almost without intermission. Sometimes, the gales would lull for a few hours, and then burst forth with renewed violence, often threatening to dismantle our storm worn ship.

Upon this icy, rock-girt shore,

Fierce tempests all their furies pour;

And angry waves successive rise,

Their foaming tops, into the skies.

No balmy zephyrs here prevail,

To lightly fan the fluttering sail;

But ice-bergs, clouds and storms so drear,

That fill the stoutest hearts with fear.

In consequence of repeated and severe storms, we were driven far to the Southward of the Cape; so that we saw no land during the whole time we were doubling the continent of South America. I think we went as far South as 63 degrees, and the weather was so cold, that we were compelled to dress in our thickest woolen clothes to keep comfortable; notwithstanding it was the last month of summer. We met with a number of small bodies of floating ice and one ice-berg so large that we were made sensible of its proximity without seeing it. On one dark and stormy night whilst we were heading slowly to the Southwest under easy sail, it became much colder than usual, and as the intensity of the cold continued to increase, our Captain concluded that we were gradually approaching an ice-berg, and fearing that we might have a collision with the floating ice, ordered the ship to be laid to until daylight. As soon as it began to get light we found that the Captain’s supposition was true; for we perceived a large white bank towards the Southwest, which in the faint light, looked like a heavy irregular cloud. But when it was fully day we found that we were about seven miles distant from a beautiful island of ice, at least five miles long on the side fronting us. We made sail and ran within two miles of the ice-berg to get a better view. The main bulk of the ice above water was at least one hundred and fifty-one feet, but many of the irregular peaks extended more than two hundred feet above the surface of the ocean. We can form a tolerable fair estimate of the vast bulk of this ice-berg by considering that it must have extended at least three hundred feet below the surface of the ocean, because ice floats with only one-third of its bulk above the surface. Nothing could exceed the splendor of this icy island when the sun shone upon it. The eastern side of its peaks were so brilliantly illuminated that they looked like highly burnished silver, so dazzling on account of the reflected light that we could not look upon them steadily for any considerable time. Whilst we were near the ice-berg we heard several loud reports, which we supposed to be the cracking of the ice, and occasionally large masses would break off from the sides, and tumbling into the ocean would make the spray fly high into the air. After stretching along the Northeastern side of the ice-berg and viewing it for several hours, we tacked ship and bore away Northwest on our passage round the Cape.

We had been nearly two weeks almost directly off the end of Cape Horn, and baffled and driven about by adverse storms that we scarcely made any progress during that time; but at length the Westerly gales abated for a few days, and the wind veering more favorably towards the South, we reached the Pacific and steered northward to cruise on the West coast of South America.

Soon after we commenced running along the coast of Patagonia, we were overtaken by a violent gale from the South, which appeared to be the severest one that I had experienced. This gale continued over three days without any perceptible abate, and so violent was it that we were not able to carry any sail but a close reefed main-topsail, and even that would have been blown away had it not been a new sail recently put on. Being wide from land, and having nothing in our way, we squared the ship before the storm, because it was favorable, and though we had scarcely any sail on, I think she ran faster than I ever saw any ship either by sail or steam. The second day of the storm it was dangerous to run, for it was with much difficulty that we prevented the ship from broaching-to. As far as our vision could extend over the ocean, nothing could be seen but the long rolling waves covered with white foam, and in the distance the flying spray appeared to mingle with the trailing clouds. Our frantic ship appeared to leap from wave to wave, and though we had double tackles upon the helm, and two picked seamen at the wheel, it was with great difficulty that she could be kept within three points of her course. After this gale ceased, nothing interesting occurred until we arrived at the Island of Juan Fernandez.

JUAN FERNANDEZ ISLANDS.

On the evening of the 12th of March the Mate informed the Captain that we were near the Island of Juan Fernandez, and if we continued running with the wind favorable we should reach the Island before midnight. Early in the night the ship was laid-to, and when morning came, the beautiful Island was seen about eighteen or twenty miles distant. The prospect was very cheering, because we had seen no land since we left St. Nicholas on the 8th of December, a period of three months and five days, and we had been much of the time exposed to rough seas and chilling tempests.

The art of navigation affords the most indubitable proof of the science of astronomy. When we consider that our ship had been cruising in two oceans for more than three months beyond the sight of land; and during that time we had sailed in various directions over twelve thousand miles, much of the time the weather being cloudy and stormy; and yet, had kept our reckoning so as to know our approach to an island in the ocean before seeing it; all this settles the question of the truth of astronomical investigations beyond doubt, for the calculations of navigation are based upon astronomy.

Our object in touching at the Island of Juan Fernandez was to get peaches. When the Chileans used this island as a place for convicts, they planted many peach-orchards in the valleys and on the plains, which were growing very thriftily when we visited the island; notwithstanding it had been abandoned by the Chileans for several years previous in consequence of a severe earthquake.

This island is celebrated as having been the lonely residence of Alexander Selkirk, a Scotch seaman who was left here in consequence of a disagreement between him and the Captain of an English ship in which he was sailing; which adventure gave rise to the very popular fiction, “Robinson Crusoe.”

Juan Fernandez sounds as if it was the name of but one island; but there are two islands included under that name. Más a Tierra is the name of the island which we visited, and supposed to be the one upon which Selkirk remained for years. This is a beautiful island about twelve or fifteen miles long, presenting broken and picturesque appearance. The shores are rocky and precipitous and the mountains in the interior are elevated three or four hundred feet above the sea. We entered Cumberland Bay in the early part of the forenoon, and not wishing to remain long we sent two boats on shore to gather fruit and then tacked about and ran out to sea, intending to go in for the boats in the afternoon. By the aid of a good spy-glass I perceived that the island was well wooded, and many of the plains and valleys appeared to be rich in pasturage. I saw several herds of horses grazing on the plains, and was told that these were owned by Chileans who suffered them to remain here in a wild state until they wanted them for use. I did not have an opportunity of going on shore with the boats, but I will give an account of the success of our fruit-gathering party and their description of the island.

JUAN FERNANDEZ.

On this lone Isle did Selkirk spend

Four years, in dreary solitude.

No voice was heard of foe, or friend,

No human rights did here intrude.

He was a Prince, whose lone domain,

Was bounded by the ocean tide:

No liveried court did he maintain,

No serf did on his mandate bide.

Late in the afternoon, our ship re-entered Cumberland Bay and the boats soon came alongside, bringing a good supply of peaches and apples, which was a delicious treat to us who had been confined for several months on salt diet. Two of our officers carried guns on shore with them, and they were quite successful in killing pigeons, which were found to be plentiful. Others of the party caught fish enough to make several messes for the whole crew.

I learned from those who went on shore, that the valleys were very fertile, abounding in fruits and wild oats. There was no volcanic appearances seen about the mountains, but the effects of the late earthquake were visible in the yawing chasms, uprooted trees, broken-down walls, and scattered fragments of the houses once occupied by Chilean officers and convicts.

Whilst sailing around this Island, my fancy pictured many thrilling scenes in connection with Selkirk’s lonely residence here. I imagined what might have been the Scotchman’s feelings, had such an earthquake occurred as that which convulsed the Island a few years before our visit.

In my fancy, I saw him in this isolated home, more than three hundred miles from the continent. He had wandered through the quiet valleys and ascended the mountain summits every day, to look out upon the deep blue ocean, until months, yea, years had passed away. During those years of dreadful solitude no human speech had greeted his ear, save the echo of his own voice from the surrounding hills, and he had almost forgotten vocal language. I fancied a time when an unusual stillness prevailed, not only over his isolated domain, but even the surrounding ocean had ceased its murmurings, as if solemnly impressed with the awful silence that prevailed, and long glassy waves passed noiselessly by like floating specters. Not a zephyr moved the pendent branches, the soft melody of the woodland songsters had ceased, and whilst a profound suspense brooded over the face of nature, his solemn reverie was disturbed by a low rumbling sound proceeding apparently from the inmost recesses of the mountains. The sepulchral rumbling increased, the earth began to tremble with quick and fearful vibrations, the affrighted beasts sprang from their lairs and darted wildly across the plains, and he rushed to the mountains for safety. How suddenly and frightfully was nature transformed! Wild gusts of wind swept through the mountain gorges, and the whole island appeared to move and tremble as if uplifted by some giant force beneath. He looked around and beheld the earth heaving and bursting into chasms, and huge cliffs tumbling over the steep precipices. He looked out upon the ocean and saw it recede as by magic, and returning with redoubled fury, dash high upon the rocky parapet, as if determined to submerged his sea-girt home.

Such thrilling phenomena, I fancied to have occurred during Selkirk’s lonely abode, and I obtained the materials for my imaginary earthquake from the description of the earthquake at Talcuahano, which was given to me by one who witnessed the sad catastrophe and the substance of which I have recapitulated as nearly as I can recollect.

This beautiful Island has many little mountain rills which afford a good supply of fresh water, and the bays and inlets abound in excellent fish. These favorable circumstances, together with the fertility of the valleys, would render this a desirable place of residence if it was not connected with the probability of an earthquake. Several years after my voyage to the Pacific, Juan Fernandez was leased from the Chilean government by a company from the United States; but I do not know what progress they have made in colonization. I presume, it would support a colony of three hundred persons and some trade might be carried on in sandal-wood, which is pretty plentiful in the Island. We did not pass within sight of the other Island of the group, Más Afuera, which is about seventy miles Westward; but steered North, intending to cruise along the coasts of Chili and Peru, and stop at the river Tumbes on the coast of Ecuador to get a supply of water and vegetables.

In my previous “Incidents” I have said nothing of the general character of the sailor; I mean the experienced sailor. Among the many who read of, and even among those who occasionally see something of seafaring life, there is very little definite knowledge concerning the sailor or his business.

It is a well established fact, that certain localities and occupations exert a transforming influence upon the characters and habits of man; and this is especially true in regard to the ocean. No man therefore, can live upon the ocean for a number of years and engage in its arduous duties, without having his character and habits considerably modified.

Among regular seamen, there is less deception than among any other class of men. This is the effect of their absence from the conventional formalities of what is called refined society, and the rivalry most commonly connected with trade and speculation. The regular sailor is frequently guilty of demoralizing practices; but it may be said to his credit, that he rarely ever attempts to cheat or deceive.

Experienced seamen are generally more intelligent than landsmen who have enjoyed no better facilities of education. Whilst many of them are illiterate; they nevertheless, possess considerable knowledge of countries, productions, people and customs, which they necessarily acquire from their intercourse with foreign nations.

The true sailor is always generous. He never meets an object of distress, without making an effort to alleviate its sufferings if the means are at his command. We might naturally expect him to be brave, when we consider the appalling dangers to which he is frequently exposed. The furious tempest which drives the landsman to his sheltered home, summons the sailor to duty. When the storm-spirit is abroad upon the ocean, whistling through the rigging and making wild sport with the enraged elements, then the sailor leaves his rocking hammock, and amidst the howling tempest and thick darkness he ascends the giddy mast whilst his ship is plunging wildly into the forming ocean. The sailor is not only fearless of danger but he is careful never to embroil himself by giving offense or unnecessary provocation. He will fight bravely at the blazing cannon’s mouth, or fearlessly attack the huge monsters of the deep, but he scorns to engage in trifling broils, or to be amused with cur-dog fights. I never knew a thorough sailor to visit a cock-pit, unless he was enticed by some vile associate during his moments of inebriation.

When the sailor arrives in port after a long confinement on board his floating kingdom, where he has endured the most rigid discipline and many privations; his long restrained passions, freed from those checks which his isolated condition necessarily impose, return upon him with irresistible force, and yielding to the overwhelming impulse he indulges in many demoralizing practices. Those who only see him on such occasions are apt to suppose that he is wholly destitute of moral principle or religion. Such conclusion would be premature and erroneous. When we consider how frequently, and for how long he is separated from social and religious privileges, and how many human vampires there are in every sea-port, eagerly watching for opportunities to entrap and draw from him his hard earnings, we cease to wonder at his moral irregularities during the few days or weeks he may spend on shore. But those who have favorable opportunities for studying the character of the sailor know that he possesses many moral and religious sentiments. There is no occupation more calculated to inspire feelings of divine reverence and devotion than the business of the sailor when disconnected from the debasing influences of ports. Far removed from the giddy whirl and excitement of the speculating and fashionable world, his mind inadvertently and frequently turns upon spiritual things. He readily forms an idea of the vastness of creation from the wide expanse and profound depth of that boundless waste of waters over which he travels for weeks and months without a single object to obstruct his view. He acknowledges the illimitable power of God in the resistless storm that sweeps over his ocean-home, and whilst he paces the lone deck during the silent watch, when darkness hovers over the face of the great deep, his mind and feelings are soothed by the soft murmurings of the waves, and all the early associations of home, parents and friends steal softly over his soul like zephyrs from a spirit land. He looks into the dark, deep ocean, and thinks of death and the grave. His steady eye penetrates the vaulted dome of Heaven, and wandering among the silent, twinkling stars he meditates upon a happy place and state of rest far beyond this world of human strife and disappointment.

In all my intercourse with sailors, I never met with one who was an infidel. If many of them are immoral and irreligious, it must be attributed to the very feeble efforts that have been made heretofore to furnish them with religious privileges and appliances. Some Christian denominations are beginning to manifest a more lively interest in the spiritual welfare of the sailor, and we may cherish the hope, that e’er long the thick clouds will be swept from his moral horizon, and his religious atmosphere will be as pure as that which rests upon his own blue sea.

I trust that my readers will pardon this digression, for I have been so deeply absorbed in my reflections upon the life and character of my old ocean-companions, I almost forget that our ship was steadily pursuing her course along the Western shores of South America.

I will now relate an incident which for a short time excited considerable apprehension for the safety of our ship. Whilst cruising off the Northern part of Chili, we experienced several successive days and nights of calm foggy weather. One night whilst we were thus becalmed, I was aroused from my soft slumbers (indeed I enjoyed many soft, rocking slumbers upon the ocean) by an unusual excitement upon deck. I soon heard the blowing of whales very distinctly, although I was ensconced in my close berth in the forecastle. I hastened to the deck and found that we were in the midst of a large school of whales. We heard them blowing and gamboling in every direction around us, but so dense was the fog that we could not see them, though it seemed by the loud sounds that some of them were only a few yards from the ship. They would sometimes leap from the water, making a loud splashing noise as they fell into the sea, and were either unconscious of the proximity of our ship, or cared nothing for us. They remained only a few moments near our ship, and as they moved off slowly in the deep gloom, their blowing and splashing softly melted in the distance, like the receding noise of some huge ghosts of the ocean.

I did not suppose that we had any just cause of dread, though some of our crew thought otherwise. If they had come in contact with our ship in their playful frolic, we would probably have experienced a considerable shock from the accidental collision, but I have no idea that it would have been sufficient to damage our ship to any considerable extent.

About eighteen or twenty years ago, the whale-ship Essex of Nantucket was sunk by a large infuriated sperm-whale. The whale had not been attacked by the crew of the Essex, but was supposed to have escaped from some other pursuers. When first seen by the crew of the Essex, it was approaching the ship at a furious rate, occasionally leaping from the water and lashing the sea violently with its huge tail and fins. The crew were preparing to lower the boats for pursuit but on observing the whale’s intention to attack the ship, the Captain ordered them to await the result. He ran against the ship apparently with all the force he could exert, striking her near the forechains, which is a little forward of the middle. The shock was tremendous, causing the ship to tremble violently from mast-head to keel. The whale retreated for a short distance, and repeated the blow, with equal force; and after vainly attempting to seize the ship with his mouth, he left her, still being much enraged. It was soon discovered that he had broken several planks above and below water, and after laboring hard to keep the ship afloat they were compelled to abandon her, and she soon sank below the waves. A similar fate happened to a ship more recently off the coast of Brazil. These are the only instances I ever heard of ships being attacked and destroyed by whales.

The circumstances connected with the fate of the Essex were related to me by a gentleman who was an officer on board the Essex at the time of the catastrophe.

Whales sometimes attack the boats which are fastened to them, but it is very seldom that any lives are lost in such attacks; for they generally content themselves with mutilating the boat, whilst the men make their escape by swimming, and are picked up by other boats that happen to be in company or near by.

SOUTH AMERICA.

We did not approach near enough to the coast of South America to see the land until we got as far up as the South-western part of Peru. We first saw the Andes when they were more than a hundred miles distant, and a considerable time before we could see the shore that was much nearer us. The Andes first appeared like pale blue clouds, and became more and more distinct until we approached within twelve or fifteen miles of the coast, when they appeared about eighty miles in the background rising in bold relief against the Eastern horizon.

Nearly the whole coast of Peru, along which we sailed for several days, presented a bold and sterile appearance, very little of it near the sea being wooded; and the lofty range of the Andes mountains in the East seemed as an immense wall to shut us out from the Eastern portion of the world.

Early in April, (I do not recollect the exact date) we arrived at the mouth of the river Tumbes. This is the place where the Spaniards under Pizarro, first landed to invade Peru.

When we arrived at the river Tumbes, we moored our ship in the open roadstead about three furlongs from the shore, because the river was too narrow and shallow for our ship to enter. A roadstead is a part of a river or bay, where there is good anchorage or holding bottom. At the season when we visited Tumbes, the weather is generally so mild that ships may safely anchor in any roadstead on the West coast of South America; but in the months of November and December when the periodic storms—called northers—prevail, it is dangerous to anchor anywhere along the coast except in well sheltered harbors.

Tumbes river is on the coast of Ecuador, and it is said to be the place where the avaricious Pizarro first landed when he invaded Peru. At this point the land is lower than any I saw along the coast, and it appeared to be very fertile and heavily wooded. There were a few huts at the mouth of the river, occupied by six or eight families who resided there for the purpose of trading with ships, and among them was a keen one-eyed Yankee. I have no recollection of visiting any inhabited island in the Atlantic or Pacific, or any place in South America, where I did not find one or more of this migratory species of the human race. The town of Tumbes, which I will describe further on in this article, is situated about nine miles up the river.

We obtained our supply of fresh water in the following manner. Twenty-five large water-casks were thrown overboard into the sea, and fastened together so as to form a long raft, which was attached to three whale-boats to be rowed into the river. When we arrived at the mouth of the river with our raft of casks, we encountered a very rapid current pouring through the narrow mouth, and the waters of the river meeting and struggling with the breakers of the ocean, produced such a whirling and foaming of the breakers that we had great difficulty in entering. Having failed in our first attempt to get through the breakers, we fell back a short distance into the smooth sea, and raising a merry boat-song, we started with redoubled efforts and soon swept our boats and raft through the foaming breakers.

When we had got several hundred yards above the mouth of the river, where the water was not impregnated with the salt from the ocean, we anchored our boats and after filling the casks, rowed back to the ship and hoisted them on board. In this manner we filled two rafts per day, and in three days obtained the necessary supply of water,—one hundred and fifty casks.

Our next business, was to get wood, and for this purpose we obtained a privilege to cut in a large forest on the right bank of the river. On the fifth day after our arrival the whole ship’s company, except a few who were left to take care of the ship, started on the wooding expedition. The one-eyed Yankee, whose name I have forgotten, conducted us several miles up the river to a tolerably good road, leading through the dense guava thickets to the forest which was more than half a mile from the banks of the river. The wood was cut by our crew, and hauled to the boats by the natives on little ox-trucks or wagons, which appeared to be the poorest arrangement for hauling that I had ever seen. The wheels of the wagons were round blocks sawed from large logs about two and a half feet in diameter, and the oxen were attached to the vehicles by a pole, or small beam passing across their foreheads and lashed to their horns. Nevertheless, they hauled tolerably good loads, and in this manner we obtained our supply of wood in two days.

The banks of this river are skirted with dense thickets of guava bushes which are fifteen or twenty feet high, and overhang the stream, so that we plucked the fruit from the branches as we passed along in the boats.

The guava bears a pretty yellow fruit about the size of a lemon. The outside pulp is mellow and tolerably good for eating, and within the pulp is a rich core which is very palatable.

Beyond the guava thickets, about half a mile from the banks of the river are extensive forests of Log-wood, Brazil-wood, Spanish-cedar, Cork &c. The Spanish-cedar attains a very large size. Many of those which I saw, were from six to nine feet in diameter. Wild flowers were very abundant in the forest. I saw several beautiful varieties of cactus, five or six feet high and in full bloom. Grouse, parrots and many gay-colored birds were numerous, and occasionally we saw wild monkeys which appeared to dispute our right to the forest by much loud squealing, chattering and grinning. The Captain and Dr. Wells killed a number of fine spotted grouse, which were about the size of common ducks, and some other nice birds for eating which resembled large snipe. The gallinule was very abundant in the guava thickets but they were so wild that our sportsmen did not shoot any.

After we had finished wooding, four boats were sent seven miles up the river to get potatoes, yams and oranges which one of the native planters had engaged to furnish us. When we arrived at the plantation we learned that the vegetables would not be ready for a considerable time, and as it was early in the day, we determined on visiting the town of Tumbes two miles higher up the river. We found nothing very interesting about the town; it was pleasantly situated on a fertile plain, and contained about twelve or fifteen hundred inhabitants. Some of the houses were built of wood, and many of adobes, which are bricks dried in the sun. Those houses that are built of adobes and plastered on the outside look tolerably well, but those that are not plastered, present a dingy and uncomfortable appearance. There is every facility about lumber for making at least tolerably good brick and building neat houses, but the absence of intelligence and enterprise prevent this mongrel race from making any advancement beyond semi-barbarism. Nearly all the inhabitants of Ecuador are Mestizos, a mixed race of Spaniards and Indians. They are ignorant, indolent and bigoted and have very little desire or capacity for improvement. Whatever commercial enterprise exists in the towns is generally conducted by Yankees or Englishmen, for the native inhabitants have very inferior talents for trade or speculation. The agricultural operations of the country were at that time conducted in the rudest manner, and I presume that very little improvement has been made since. The only kind of plow that I saw was made from the limb of a tree, or a root very roughly hewn, having a small piece of iron fixed on the end with which they scratched the ground.

Such a large portion of Ecuador is mountainous that a comparatively small part is susceptible of cultivation, and much of that which would admit of cultivation is covered with dense forests; but the land that is cleared in the valleys and along the rivers is so fertile, that it produces good crops of corn, sugar cane, rice, potatoes, yams, &c. notwithstanding the rudeness of their implements and their obstinate adherence to old customs. I learned from some of the most intelligent inhabitants that excellent wheat was raised upon the elevated table lands, where almost perpetual spring prevails. The collection of Cinchona, or Peruvian Bark from the forests at the foot of the mountains is the most enterprising business of the state, and I observed that considerable quantities of this bark were stored at lumber to be transported to Guayaquil ,the only seaport town of Ecuador.

When our boats’ crews assembled to depart from lumber, two of our men, a Portuguese and a young man from New York, could not be found. After searching for them diligently, the Mate, being satisfied that they had deserted, offered a reward for their arrest. We then proceeded down the river, took on our vegetables and arrived on board the ship just after dark.

Our Captain determined to wait two days for the arrest of the deserters, but the next day after they absconded they were brought to the ship, having been taken in a forest near the town. The young man from New York said that he was induced to desert by the persuasions of the Portuguese, and he was willing to resume his duties and complete the voyage. No punishment was inflicted upon him, but the Portuguese positively refused to return to duty, and being wholly insubordinate, he was handcuffed and put on short allowance until he acknowledge his fault and expressed his willingness to return to duty.

The marine laws of our country are very strict. When a seaman has signed articles of enlistment for a voyage to a foreign port, he cannot leave the ship until she returns to the United States unless he is discharged by an American Consul on account of sickness or some disability. In such a case the Consul is compelled to take charge of the sick or disabled seamen, have him attended to, and send him home if he requests it. If a seaman deserts his ship, the captain or a consul can have him arrested and imprisoned, or inflict corporal punishment so as to make him resume his duties.

Having obtained the necessary supplies, we sailed from Tumbes roadstead intending to cruise along the Equator until we arrived at the Galapagos or Tortoise Islands. As we passed along the coast of Ecuador, we saw the three most remarkable mountains in South America: Pichincha, Chimborazo and Cotopaxi. Chimborazo rises like a huge giant above the surrounding peaks, and was long regarded as the highest mountain in the world; but several mountains in Asia and one or two in South America have been discovered to be higher. Pichincha and Cotopaxi are celebrated volcanoes. The eruptions of Cotopaxi have been heard a hundred and fifty miles like the firing of heavy artillery. When we saw it, large columns of smoke were rising from the crater and hovering over the summit, but it was not in active operation.

Here giant mountains in succession rise,

Whose snow-capped summits kiss the ambient skies;

Volcanoes belching with a thundering sound,

The flames that kindle far beneath the ground.